Western IT understands that Business IT Services and Business Cybersecurity require varied knowledge and skills. Local Perth...

Western IT understands that Business IT Services and Business Cybersecurity require varied knowledge and skills. Local Perth...

Cybersecurity in Michigan The Importance of Cybersecurity in Michigan. cybersecurity stands as a cornerstone of organizational...

Navigating Cyber Insurance: Mitigating Risks and Maximizing Protection 1. Risk Mitigation through Expertise2. Access to...

Managed Equipment Services Managed Equipment Services. Efficient, reliable, and secure IT infrastructure is paramount. Companies...

IT Recovery Solutions have become crucial to business continuity and data management. As enterprises increasingly rely on...

Cyberattacks on Canadian Health Systems. In the rapidly evolving digital landscape of 2023, the Canadian healthcare sector has faced unprecedented challenges in the realm of cybersecurity. This comprehensive report delves into the critical issue of cyberattacks targeting health information systems across Canada, a concern that has escalated both in frequency and severity in recent times.

As we transitioned further into the digital age, the healthcare sector’s dependency on electronic medical records (EMRs) and digital tools has exponentially increased. This digitization, while streamlining healthcare delivery, has also rendered the sector highly vulnerable to cyber threats. The year 2023 has been particularly significant in highlighting these vulnerabilities, with an alarming surge in the number and sophistication of cyberattacks.

Canadian health systems have digitized considerably. In 2019, 86% of surveyed Canadian family physicians reported using electronic medical records (EMRs).1 Digital tools for virtual care and remote patient monitoring, wearables, care coordination platforms, and Internet-of-things (IoT) devices are all permeating practice.2 The digitization and integration of disparate health information systems on shared networks promises greater convenience, access and quality of care, but also introduces risk for patients, providers and health systems. Although some clinicians have dedicated information technology (IT) training, most do not, and navigating increasingly complex health information systems can create considerable stress.

Cyberattacks can incur privacy breaches and financial harm, as well as compromise patient safety and health system functioning. Personal health information (PHI) can fetch much higher prices on the dark Web than other personal information (e.g., credit card details).3 In a 2021 international survey of health IT decision-makers, the average cost of a ransomware attack was US$1.27 million. 4 Cyberattacks against health information systems have been associated with delays in care, diversion of patients to other sites and increased mortality.5 Cyberattacks against Canadian health information systems are increasingly common, with 48% of all reported 2019 Canadian breaches occurring in the health sector.6 Cyberattacks have also been increasing amid events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russo–Ukrainian War.7,8 We outline the impact of cyberattacks on Canadian health information systems and how clinicians, whether they practise in large hospitals or individual clinics, can improve their cybersecurity posture.

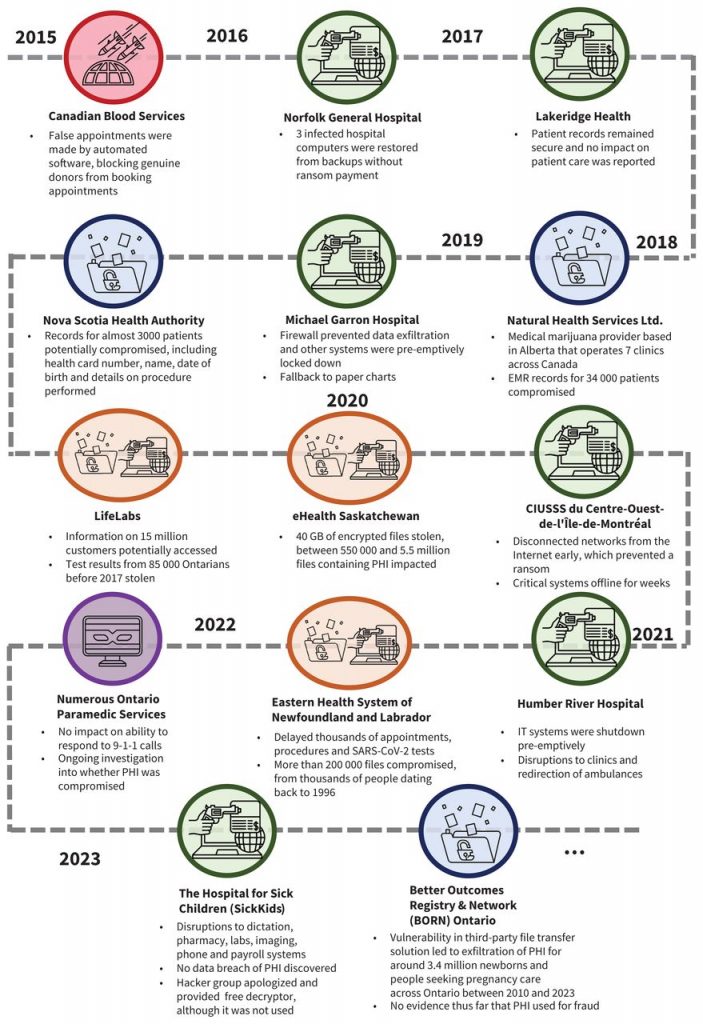

Cyberattacks against health information systems are most commonly ransomware or data breaches (Figure 1). At least 14 major cyberattacks on Canadian health information systems have occurred since 2015, 9 of which attempted ransom and 6 of which compromised PHI. Ransomware involves the installation and activation of a malicious program (i.e., malware) that locks or encrypts a computer system and its stored data until a financial ransom is paid. Access to data is commonly lost even when ransoms are paid.4 The attack can also entail data breaches, whereby PHI is exfiltrated off health information systems and shared illicitly in online marketplaces. Another form of extortion relies on denial of service, whereby an attacker overwhelms a site through fake traffic to make it unavailable for authentic users (e.g., patients attempting to book an appointment) until a payment is made.9 Although most cyberattacks against health organizations are attributed to criminals, they can also be perpetrated by nation-states, terrorist groups, online “hacktivists” and ideologically motivated violent extremists (e.g., those targeting abortion centres).10–12

The passage highlights the vulnerability of health organizations to cyberattacks, emphasizing their attractiveness as targets for several reasons:

The passage also contrasts the response to ransom demands between Canadian and American health systems, noting that while Canadian hospitals have not been reported to pay ransoms, American health systems have paid substantial amounts, sometimes in the millions of dollars. Even without a payment, the mere attempt at extortion can cause significant operational disruptions, impacting both IT infrastructure and patient services. This situation underscores the critical need for enhanced cybersecurity measures and robust response strategies in health organizations.

A comprehensive comparison of the burden of attacks between jurisdictions is difficult since many cyberattacks on health information systems are unreported.15 Although effective cyber-hygiene (i.e., daily routines, good behaviours and occasional check-ups akin to principles in health) strategies for end-users are essentially universal across organizations, sectors and jurisdictions, cybersecurity policy in Canadian health information systems has considerable room for improvement.

In June 2022, the House of Commons proposed the Critical Cyber Systems Protection Act (CCSPA). The CCSPA defines critical cyber systems as those with serious implications for public safety if compromised. These systems include telecommunications, pipelines, nuclear energy, federally regulated transportation and banking — but not health organizations.16 In contrast, the United States Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency supports a range of Sector Coordinating Councils that collaborate with the government for information sharing, coordination and the establishment of voluntary practices to promote resilience.

The Healthcare and Public Health Sector Coordinating Council has dozens of members, including health systems, advocacy groups, insurers and nonprofit organizations.17 Although the exclusion of health organizations from the CCSPA could be viewed as consistent with the federal–provincial principles of the Canada Health Act, governance mechanisms such as Sector Coordinating Councils could promote adherence to common standards while also fostering innovation and experimentation.

Within the provinces and territories, considerable heterogeneity exists in cybersecurity posture among broader public sector organizations, as smaller institutions often lack requisite financial and human resources.

Shared services models can help address disparities. For example, Ontario Health is piloting 6 regional security operation centres.18 Each centre would continuously monitor the security practices of member institutions, defend against breaches and proactively isolate and mitigate security risks. Regional security operation centres are similar to the well-received, health-related computer emergency response teams in the United Kingdom, Norway and the Netherlands.10 As governments establish these bodies, clinicians and health organizations must develop familiarity with them and their incident reporting and escalation pathways. During establishment of these bodies, governments should also endeavour to engage clinicians to ensure their needs and perspectives are considered. Provinces and territories should be wary of regulating cybersecurity practices beyond reporting at the level of the individual provider or health organization (e.g., mandating biannual cybersecurity audits) as top–down requirements can be overly onerous in terms of effort, capital and human resources, especially for smaller practices.

Finally, provinces and territories should establish publicly available repositories of cyberattacks on health information systems.15 Such repositories can serve as a useful aid for research and guide consumer choice as patients may preferentially seek out providers with strong cybersecurity track records.

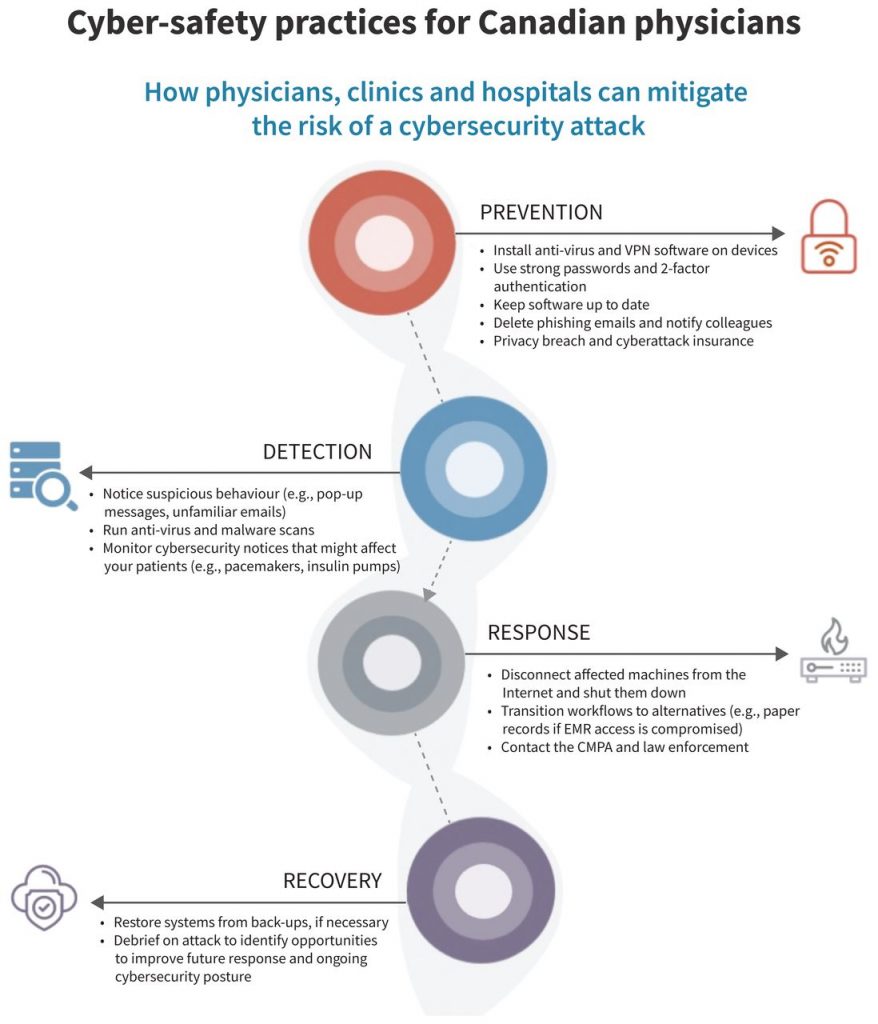

The US National Institute of Standards and Technology outlines 5 stages to effectively navigating cyberattacks: identification, protection, detection, response and recovery.19 For simplicity, we have combined the stages of identification and protection into a single prevention stage (Figure 2).

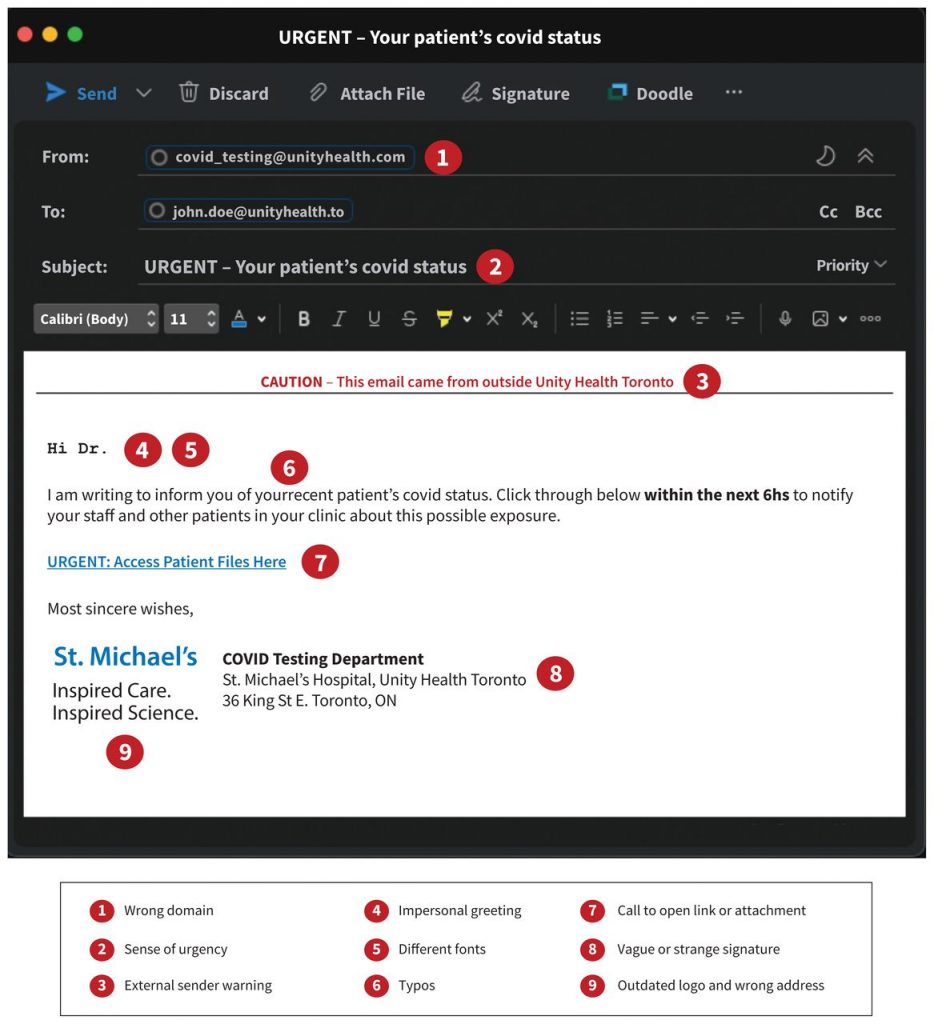

At the individual level, cyber-hygiene prevents attacks. Clinicians should be vigilant for phishing attacks via email or other suspicious behaviour (Figure 3). Phishing refers to targeted, deceptive efforts to gain access to a victim’s device or network. Once access has been obtained, an attacker can install malware to exfiltrate or encrypt data for ransom. Clinicians should ensure they use unique, strong passwords (i.e., at least 8 characters with a mix of letters, numbers and special characters) and 2-factor authentication for their logins, as well as set up verification questions and auto-lock devices with access to PHI. Password managers can generate and store unique, strong passwords for each site and provide notifications when user information is compromised.

Clinicians should avoid sensitive tasks without adequate network protections (e.g., accessing patient records on public Wi-Fi) as data can be intercepted or malware can be installed in “man-in-the-middle” attacks. Software must be kept up to date as developers release patches for security vulnerabilities on an ongoing basis. Health organizations are notorious for relying on legacy systems (e.g., Windows XP) well past the date of their security support deprecation.

At the institution or practice level, a key aspect of preventing cyberattacks is to reduce the attack surface, or the number of entry points an intruder would have into health information systems. This is especially important with setups in which individuals can use their personal devices and with increasing numbers of IoT devices.20 Techniques for reducing attack surfaces include auditing all devices on the network, ensuring that their software (including operating systems) is up to date, installing antivirus and antimalware software, and setting up a firewall to monitor both outbound and inbound Internet traffic. Practices can also set up a virtual private network (VPN), which encrypts and disguises online traffic, making it much more difficult to intercept. Virtual private networks are particularly important for clinicians who wish to access PHI from environments outside their health organization’s network, such as to complete charting at home.

Although clinicians in larger organizational settings will have the benefits of a standardized approach, those in private practice will have to rely on third-party vendors. Luckily, many traditional antivirus vendors now have comprehensive bundles of services. Professional support from organizations such as the Ontario Medical Association exists, including privacy breaches and cyber coverage to assist with forensics, public relations and legal services. These should be viewed as essential office expenses and, in many jurisdictions, may be eligible for tax credits.

Suspicious behaviour can indicate a cyberattack. Examples include barred entry to files or applications (e.g., EMRs, email clients), the deletion or installation of unrecognized files and software, program auto-running and emails sent without the user’s consent. Ransomware attacks are often accompanied by pop-up messages that indicate to the user that they are being hacked and that provide instructions and a deadline for ransom payment. Antivirus or antimalware software can also detect threats on routine scans. Finally, users within the organization may report that they followed a link in a phishing email or downloaded unknown files or applications.

Once a cyberattack is detected, clinicians should first disconnect affected machines from the Internet and shut them down. Quick action can prevent the exfiltration of data, including PHI, from a health organization’s device and network. Once this is done, practices should activate their cyberattack response plan. If access to computerized systems such as EMRs is lost, staff should transition to back-up workflows such as using paper records. Depending on the magnitude of workflow disruptions and the ability of clinicians to maintain an adequate standard of care, contingency measures such as cancelling clinics and transferring patients may be needed. Crucially, response plans should not be improvised but rather be well documented, clear and deliberately practised.21 Clinicians should practise their cyberattack response (i.e., their code grey) like they would a fire (i.e., their code red). Although the pressure to do so may be immense, health organizations should generally not pay ransoms to unlock and decrypt systems, because restored access is not guaranteed and paying ransoms may encourage future attacks.

The Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) outlines the duty of custodians to notify affected individuals of privacy breaches (e.g., patients), as well as the provincial or territorial privacy commissioner and Ministry of health.22 As the nuances of expectations vary across jurisdictions, the CMPA recommends organizations and clinicians initiate contact with the CMPA as soon as possible after a possible breach is discovered. They should also contact law enforcement, especially in the event of a ransomware attack. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police is currently pilot-testing a National Cybercrime and Fraud Reporting System.23 The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security also has a reporting system; however, it does not trigger an immediate response by law enforcement.24 As part of their cyber response plan, practices should consult relevant authorities in advance to ensure they clearly understand the obligations for breach reporting and notification of law enforcement for their jurisdiction.

After the acute threat of a cyberattack has subsided, clinicians and their organizations can then enter the recovery phase. Recovery is heavily dependent on having health information systems that allow for restoration from back-ups. For smaller organizations and independent practices without dedicated IT experts, clinicians should ask how their vendors will protect their data and help recover it in case of an attack as part of their due diligence when making a purchase. Organizations should also have a focused debrief on the response, with emphasis on opportunities for improvement and measures to improve ongoing cybersecurity posture.

Clinicians may feel that adhering to the outlined actions only adds to the burden imposed on them by health information systems. In his famous The New Yorker essay, Atul Gawande quipped that the EMR systems “that promised to increase my mastery over my work [have], instead, increased my work’s mastery over me.”25 Especially for clinicians in smaller practices, cybersecurity can become another dimension of task load, in addition to documentation, computerized order entry and maintenance of licensing requirements through mandatory e-modules, all of which contribute to burnout.26,27 Simulation training has also become commonplace in medicine and some may ask if more are necessary. Measures such as 2-factor authentication and VPNs add complexity to workflows; however, small changes to daily practices that promote cyber-hygiene are far preferable to recovering from a cyberattack operationally, both financially and in terms of patient and community trust.

Preventing cyberattacks involves navigating trade-offs between keeping workflows efficient and reducing risk amid threats that are growing in frequency, severity and sophistication. As national and regional policies develop, health organizations, practices and individual clinicians must take a proactive approach to improving their cybersecurity posture. Methods for handling personal and professional risk go hand-in-hand, including leveraging tools and best practices, being vigilant and having an incident response plan. With respect to cybersecurity, a bit of prevention is worth a terabyte of cure.

Western IT Group, a leading provider in the realm of information technology solutions, stands at the forefront of combating cyber threats in today’s digital landscape. Specializing in robust cybersecurity services, they offer a comprehensive suite of solutions tailored to protect organizations from the ever-evolving nature of cyberattacks.

Their services are particularly crucial in safeguarding against threats like ransomware, data breaches, and phishing attacks. Western IT Group’s expertise lies in implementing advanced security measures that include state-of-the-art firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and endpoint protection. These tools are pivotal in creating a secure IT infrastructure, capable of thwarting potential attacks and safeguarding sensitive data.

Moreover, they offer regular security audits and vulnerability assessments, crucial for identifying and rectifying potential security gaps. Their commitment to staying abreast of the latest cybersecurity trends and threats ensures that their clients receive the most updated and effective protection.

In addition to technical measures, Western IT Group emphasizes the importance of user education and training. They provide comprehensive training programs to educate staff on best practices in cybersecurity, understanding the critical role that human factors play in maintaining a secure digital environment.

In summary, Western IT Group’s services offer a robust defence against cyber threats, combining cutting-edge technology with strategic planning and user education, ensuring their clients’ digital assets are well-protected in an increasingly vulnerable digital world.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) licence, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original publication is properly cited, the use is noncommercial (i.e., research or educational use), and no modifications or adaptations are made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Download PDF Cybersecurity and Managed IT Services Understanding What is Cybersecurity? Cybersecurity refers to the...

Western IT understands that Business IT Services and Business Cybersecurity require varied knowledge and skills. Local...

Cybersecurity in Michigan The Importance of Cybersecurity in Michigan. cybersecurity stands as a cornerstone of...